TRAINING: How Effective Is Your Young Worker Training Program?

At this time of year, your company may either be hiring or have already hired teenagers to work for it over the summer. You may have also hired recent high school or college graduates for permanent positions. So if your workplace didn’t have any before, it may now include a number of “young” workers—that is, any worker under age 25. Although BC is currently the only jurisdiction that specifically requires employers to provide special safety training for young workers in its OHS laws, such training is strongly recommended.

We recently spoke to Yvonne O’Reilly, an OHS consultant and member of the OHS Insider Board of Advisors, about a young worker training program that she was asked to update and improve. Seeing how one program for young workers was made more effective can help you improve your own program—or start one off on the right foot.

OHS Law & Young Workers

BC aside, companies in Canada technically don’t need to provide special young worker training to comply with OHS law. (Saskatchewan does require youths age 14 and 15 to take a government-provided online course certifying them as ready to work. And some jurisdictions’ OHS laws do require a safety orientation for all new workers, which would apply to any young workers you’ve recently hired.) But there are two reasons you should provide special training for young workers:

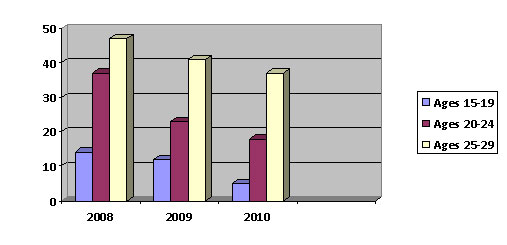

> Young workers are a particularly vulnerable group in the workplace. Every year, 48,000 young workers are injured seriously enough to require time off work. (See the graph below on young worker deaths) And the Dean Commission in Ontario specifically noted that young workers are a vulnerable group in need of special protections. By providing special safety training for young workers, you can reduce the risk that they’ll get injured.

> Even jurisdictions that don’t specifically require young worker training recognize that these workers are vulnerable and need special attention and protections. For example, Alberta has conducted inspection blitzes designed to safeguard young workers, Ontario just announced it’s conducting young worker inspection blitzes this summer and SafeManitoba recently released two new young worker safety tools. So jurisdictions may expect employers to provide safety training to young workers either under the general duty clause or as a best practice.

Problems with Prior Young Worker Program

O’Reilly’s client is a post-secondary school that hires its own students for a variety of positions. Post-secondary institutions offer a wide variety of programs and the complexity of running these environments has been compared to operating small cities. So creating a young worker training program that applied to students working, say, in labs, painting classrooms, on movie sets and in nursing homes was a challenge. After all, these workers face a wide range of hazards, notes O’Reilly. And because of the number of departments that hired students and their autonomy to do so under a variety of programs (summer, part-time, co-op, intern, etc.), there wasn’t one central database to determine how many students were working for the school at one time.

The prior young worker training program was a half-day session at which a lot of material was handed out, says O’Reilly. Much of this information was the same as what fulltime employees got, which was a red flag for her because it didn’t address the unique perspective of young workers. In addition, the material covered lots of different hazards, primarily in some high risk areas, but with little detail. At the end of the session, student workers walked away with a big binder. But O’Reilly wondered whether the school could demonstrate that they ever looked at it.

Another problem with this program, says O’Reilly, was that it wasn’t clear if there was any follow-up to ensure that workers absorbed their training. And there were few documents to demonstrate what was done in the training session. Plus, supervisors had no documented role in it.

A senior manager at the school was looking into liability issues and asked, “Can we demonstrate we’re taking care of our student workers’” When the answer was no, O’Reilly was brought in to revamp the student worker training program.

Changes to Make Program More Effective

O’Reilly made many changes to the program in several areas:

Substance. The biggest change O’Reilly made to the program was changing it to “safety awareness training,” shifting the focus from specific hazards to workplace safety in general. The program did address some types of hazards that applied to various kinds of work, such as ergonomics. But at the end, the student workers were sent back to their supervisors for hazard- and job-specific training. As a result, student workers were given just a folder—not a big binder.

The heart of the safety training, says O’Reilly, was “seven things you need to know,” such as the roles and responsibilities of employers, supervisors and workers and what to do if they have a safety concern. The original template was developed by the Ontario WSIB’s Young Worker Awareness Program and was customized for the school. (See the box below for all seven.) They explained these key things and tied them to the OHS laws. The goal was to get the attendees to stop thinking of themselves as just students and to start thinking of themselves as workers, she explains. Once they were hired as employees, the school’s obligations to them changed—and so did their responsibilities. For example, a mere student could walk past a slip-and-fall hazard and do nothing about it. But a student worker was expected to address the hazard or bring it to his supervisor’s attention.

Style of training. O’Reilly presented safety information in the training sessions in various ways and tried to make the program interactive and engaging. For example, at the beginning of the program, student workers filled out a safety-related crossword puzzle to “break the ice.” She also encouraged the students to relate their experiences from prior jobs. And she showed several types of videos, such as “true worker” stories from WorkSafeBC. One video that was especially effective, she says, was of the classic candy factory conveyor belt scene from the TV show “I Love Lucy.” O’Reilly had students identify hazards and safety measures in the scene and used it to start a discussion on supervisor responsibilities by talking about how the supervisor in the show behaved. At the end of the half-day training program, student workers were given a quiz to test their knowledge.

Promotion. Efforts were made to better promote the training to ensure that as many student workers as possible attended. O’Reilly says they promoted the training in the on-line newsletter, emailed information about it to managers and members of the JHSCs and posted information on bulletin boards. The promotions explained why the school was providing the training and why student workers were required to attend. The increased promotion also helped the school identify the number of students hired and make plans for increasing the tracking and training efforts in 2013.

To further increase attendance, O’Reilly notes that they offered the training at various sites and different times to make it as convenient as possible. They also offered a few specialized sessions for large groups of students from a particular program or department, such as facilities, media arts and elder care, to allow these work environments to be addressed in more depth.

Feedback on the New Program

O’Reilly says they trained about 200 student workers in the new program, compared to less than 100 in the previous recent years. Some of these students had gone through the prior program. These students said that although they couldn’t relate to a lot of the material in the old program, after participating in the new one, they now understood their role and how they fit into the larger workplace safety picture, she says. Several supervisors also attended the new training program and had positive comments on it.

O’Reilly adds that they shared information on the number of students trained and what they were trained on with employees at each campus location. Several people printed this information out and posted it in their departments, which she took as a good sign.

In the end, O’Reilly says the school ended up with a young worker training program that approached the legislation, the school’s program and the students’ role in a way that better suited their perspective and allowed the school to demonstrate it had provided such training and verified the students’ knowledge.

Bottom Line

O’Reilly says there are several lessons a safety coordinator can take away from her experience with the school’s young worker training program. For instance, remember your audience. Young workers are different from older workers. So you need to ensure they can relate to the training and materials.

In addition, supervisors are a key component of young worker training, she explains. You must make it clear their role and duties as to training, particularly that they’re expected to provide the hazard- and job-specific training.

INSIDER SOURCE

Yvonne O’Reilly, CRSP: O’Reilly Health and Safety Consulting; (416) 294-4141; www.ohsconsulting.ca; info@ohsconsulting.ca.

7 Things Young Workers Need to Know

1) What you don’t know can hurt you.

2) What you do know can help you.

3) The law protects all workers with the right to know the hazards in the workplace, the right to participate and the right to refuse unsafe work.

4) The OHS law sets expectations for employers, supervisors, JHSCs and workers.

5) You can expect your employer and supervisor to give you the information, training and equipment you need to protect yourself.

6) You must tell your supervisor if you get injured or sick on the job or are aware of a near miss incident that could’ve resulted in an injury.

7) Don’t take risks with your health and safety—or anyone else’s!

Source: Ontario’s WSIB

Number of Young Worker Deaths

Source: AWCBC

Source: AWCBC